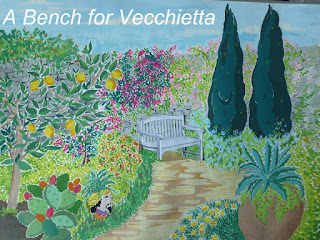

A BENCH FOR VECCHIETTA - PART 5

You

had gone, Vecchietta, just hours before, to that cold, grey, rainy

country of yours. Your sister and brother-in-law had arrived in

Sicily to take you home. That, they later told me, was what you had

wanted – to live your last days in the country that had borne you,

to hear the rain against the window pane and the sparrows in the

morning once again – and perhaps not to create a fuss, Vecchietta.

You wanted no fuss and ceremony at the end, you had once told me.

Why,

Vecchietta, did I not just get my van, turn around and drive straight

back to Catania and the airport? I wanted to and if I'd known before

I arrived in Centochiese I might even have got myself on the same flight.

Looking for someone to blame, I cursed my local friends for not

contacting me before I set off from Milan. Why had no one sent a

message, told me on social media, called me? But we Sicilians are

basically a word-of-mouth people, Vecchietta, as we have been for

generations. We don't even expect to see a bus timetable displayed at

a bus stop – well, not a current one, anyway – and even if we do,

we don't trust it. We prefer to ask someone about the arrival times.

And what we don't know in Sicily, we don't know. I was still a fool

Vecchietta. I still thought there would be time. Yes, there was all

that but, to tell the truth, as I now must, I was scared, Vecchietta

– scared to face your sister, after what I had done to you.

Will

you believe me if I say I was looking for flights the day your books

came? Boxes and boxes of them – around 4,000 volumes in all. You'd

laugh, Vecchietta, if you knew I had to build an extension to my

workshop to house them all. There they all were, in several

languages. And I, Cicciu the carpenter, who had never read anything I

didn't have to, began reading them. Once I started, I couldn't stop

but there was another reason, Vecchietta: I thought that if I read a

lot of them, then when I came to you, I could tell you about them,

and you would be proud of me.

I'd

read sitting near my window during the long lunchtimes, after I'd

eaten my plate of pasta:

“Chi

sta faciennu Cicciu?” the few friends who passed by at that

time would ask each other. (“What's Cicciu doing?”)

“Sta

ligiennu. Sta nisciemu pazzu”, I'd hear. (“He's reading. He's

going mad.”)

Or

I'd read on my balcony when the heat of the day had given way to the cool evening.

“Cicciu,

camina 'ccu niautri o' bar”, my friends would shout. (“Come to

the bar with us!”)

I'd

shake my head and they'd shrug their shoulders and sigh, “Pazienza”

before walking on.

Where

did I start with all those books? With the Italian ones, of course:

what you had read and your margin notes – you'd once told me your

books would be absolutely unsaleable because, teacher-like, you'd

scribbled notes all over them – told me so much about you and

sometimes it was as if you were here beside me:

Inside

your copy of the Inferno I found an old slip of paper

containing what must have been some teaching notes: there was a list

of names of notorious figures from your country in the 1980s and a

question about where students would put them in a vision of hell.

What a way to introduce Dante! There were several volumes of our

Pirandello and I remember that you said you had visited his

birthplace in Agrigento. Pirandello, the great master of the nature

of truth. Your favourite , among his plays, was Enrico IV. In

your copy of Fallaci's Letttera a un bambino mai nato I

learnt, from your notes, how much you had wanted children. On that

you had been totally silent, Vecchietta, which I now realise meant

that the pain ran deeply.

Inside

your copy of the Inferno I found an old slip of paper

containing what must have been some teaching notes: there was a list

of names of notorious figures from your country in the 1980s and a

question about where students would put them in a vision of hell.

What a way to introduce Dante! There were several volumes of our

Pirandello and I remember that you said you had visited his

birthplace in Agrigento. Pirandello, the great master of the nature

of truth. Your favourite , among his plays, was Enrico IV. In

your copy of Fallaci's Letttera a un bambino mai nato I

learnt, from your notes, how much you had wanted children. On that

you had been totally silent, Vecchietta, which I now realise meant

that the pain ran deeply.

I

also did something you had advised me to do many times after our

lessons: to peruse an Italian grammar explained in English. This

gave me a new perspective, Vecchietta and I learnt things I had never

realised about my own language and the difficulties it poses for

others..

As

my English improved, I began to tackle your English books, slowly at

first, with children's tales, as you had told me to do, not because

the grammar in them is easier – it isn't, necessarily – but

because I was likely to know the story. Then I progressed to other

volumes whose story I knew – classics and some books about Italian

history.

When

I came to your Shakespeare I knew I wouldn't understand it and on the

page where the Sonnets began I found a note to me.

“Cicciu,

this time you have permission to use a translation but make sure it's

a good one, now, done by a qualified person, not a machine!”

You

had directed me to Sonnet 116. Highlighted were the lines,

“Love's

not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle's compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.”

Within his bending sickle's compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.”

I

was reading it when the phone rang one evening, Vecchietta, and your

sister told me you had left this sad old world that morning. And yes,

there had been birdsong and yes, there had been rain on your

windowpane. I hope there was a rainbow, Vecchietta.

To be continued

Comments

Post a Comment